Can superhuman AI help us improve?

discussing data from the game of Go

- 13 minutes read - 2639 words

As AI continues to improve at writing and math-based tasks, it seems plausible that it either has or soon will surpass domain experts in some of these tasks. This post aims to explore to what extent superhuman AI in a domain can instruct and empower humans to improve for themselves.

The paper Superhuman artificial intelligence can improve human decision-making by increasing novelty (Shin et al.), published in 2023, explores precisely this question. The authors choose to examine these impacts through the game of Go, as it was famously conquered by computers back in 2016. More importantly, open-source superhuman engines have been widely available since 2017, along with interactive UI’s that allow players to learn from the AI’s choices. This makes Go an interesting candidate to examine the extent to which access to a superhuman entity can help humans evolve and improve.

As a case study, Go is particularly close to my heart as I am myself a competitive Go player and regularly use AI for practice and game reviews. It is my domain knowledge that leads me to disagree with the paper’s conclusions that there is evidence that human experts now perform better than in the pre-AI era. I think their own data should be interpreted as suggesting that Go AI has a minimal impact on human performance. At the end, I’ll zoom out and discuss AI’s relationship to human improvement from my personal experience in the competitive scene.

Discussion on Shin et al.

Summarising their point

The paper uses a database of over one-hundred thousand expert (professional) games. The researchers measure the development of their metrics ‘decision quality’ (DQ) and ’novelty’ in expert games between 1950 and 2021, and observe that both have statistically increased ever since the advent of AI. Moreover, the authors run a regression analysis that finds a significant positive correlation between the novelty of a move and its decision quality. This, the authors feel, justifies the thesis of the paper - that human decision quality has improved after AI’s arrival, and that it has specifically improved because players have become more creative and more novel.

My critique

The DQ of a human move k is a score based on how much worse it is (according to AI) than the favourite AI move. It uses the following formula:

\( DQI(a_{k}^{human}) = 100 - (Q(s_{k}, a_k = a_{k}^{AI}) - Q(s_{k}, a_k = a_{k}^{human})) \)

where $a_{k}^{human}$ is the action (move) chosen by the player, $a_{k}^{AI}$ is the optimal choice given by AI, and \(Q(s_{k}, a_{k}) \in [0, 100] \) is the ‘Q-value’ usually referred to by Go players as the ‘win-rate’ of a move $a_k$ from the state (board position) $s_k$. The qualitative meaning of the formula is that a human move that matches the AI will get a DQ score of 100, whereas a human move that doesn’t match the favourite AI move will have its DQ penalised by however worse its Q-value was than the ‘optimal’ AI decision.

In the appendix of this paper, the researchers justify using previous work that the metric is a ‘good’ one, in that it robustly seems to hold up against several sanity checks. For example, it distinguishes clearly between human and AI play, and can differentiate an expert from an expert who is cheating with an AI. I indeed agree that DQ more or less measures what it’s supposed to measure, and while there is an issue I have with its definition, it is minor to the principal point of this post and shall only be discussed at the end.

Their measure of novelty will also be important for the rest of this post, as Shin et al. use it in various ways to justify and explain some of their other findings. The novelty of a game is defined (suspiciously) simply by the paper. It is sixty minus the move number which featured the first move that had never previously been seen in the database. As we will discuss below, this notion of novelty adapts badly from chess, where it is commonly used, to Go.

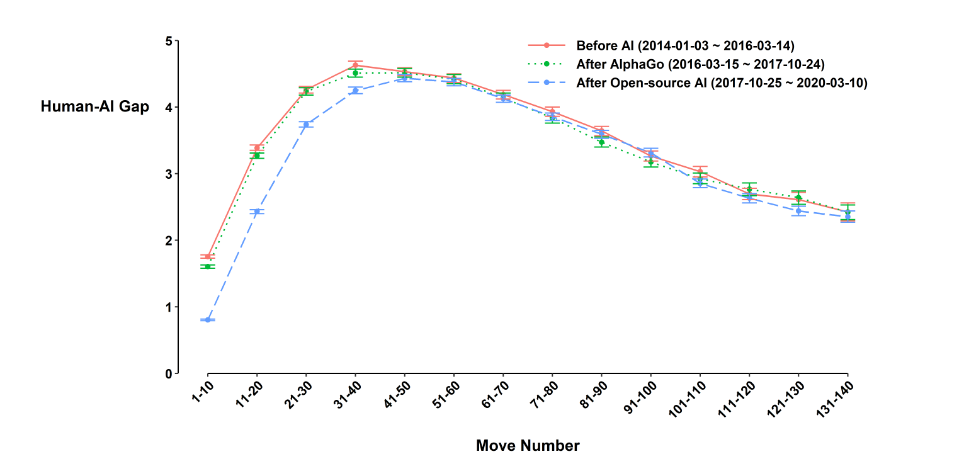

A very similar variant of DQ was already introduced in a 2021 paper (Shin et al. 2021) by a related group of researchers. It was noted that according to the metric, human expert performance had improved, but only up to move 601. The researchers use this finding to only consider human play until move 60 in the 2023 paper. This decision makes the research less interesting for a Go player. The first sixty moves are almost never decisive and rarely even give players any meaningful advantage. Most of the early game in high-level play is filled with pre-determined theoretical variations (‘joseki’) that players learn by heart. In a typical tournament game, I will have to make no more than five to ten decisions before move 60, and these decisions are much less important on average than those made later in the game. For a Go player, the natural way to interpret the data is that players have not improved in the key stages (post move 60); they only improved their score in the early game as they are memorising the AI’s favourite variations. This explanation clashes with the authors’ conclusions. They acknowledge this alternative ‘memorisation’ hypothesis and test it in several ways. While they end up rejecting memorisation as a likely explanation, I find none of their rebuttals convincing.

Shin et al. suggest that if memorisation were a good explanation for increases in decision quality over time, then this increase would no longer be statistically significant for moves after players deviate from likely memorised optimal AI choices or play a novelty. Moreover, they claim that if memorisation explained the increase in quality, then this increase would drop off ’later’ in the game2. They remark that none of these effects occur: their DQ metric still shows statistical improvement in all of the specific cases.

I argue that all of these tests actually completely miss the point, and this is because their premise fundamentally misunderstands how memorisation works in the game of Go. In chess, the entire board position is important to the next decision, and the limited board size makes memorisation of whole positions both feasible and sensible. Consequently, when a novelty is played in chess, it really is possible that a player is working in a situation they either have not memorised or can’t remember. In such a case, observing a player’s ‘reaction’ to a novel move is a meaningful thing to do.

Conversely, in Go, the center of the board tends to be empty and unimportant during the early game, as players take the corners and sides first. Memorising whole-board variations just isn’t something people do in Go at all. Instead, they memorise local variations (josekis) in important sub-regions that are initially disconnected from each other. While global thinking in Go is important, it only becomes complex or crucial way later into the game where memorisation is absolutely infeasible. Thus, there exists almost no notion of a ‘full-board variation’ in Go. This means that even though board states on move 21 are technically novel 99%3 of the time, expert players at that stage still generally play the game entirely on autopilot. They use their memory to play local variations which do not meaningfully interact with each other in early stages.

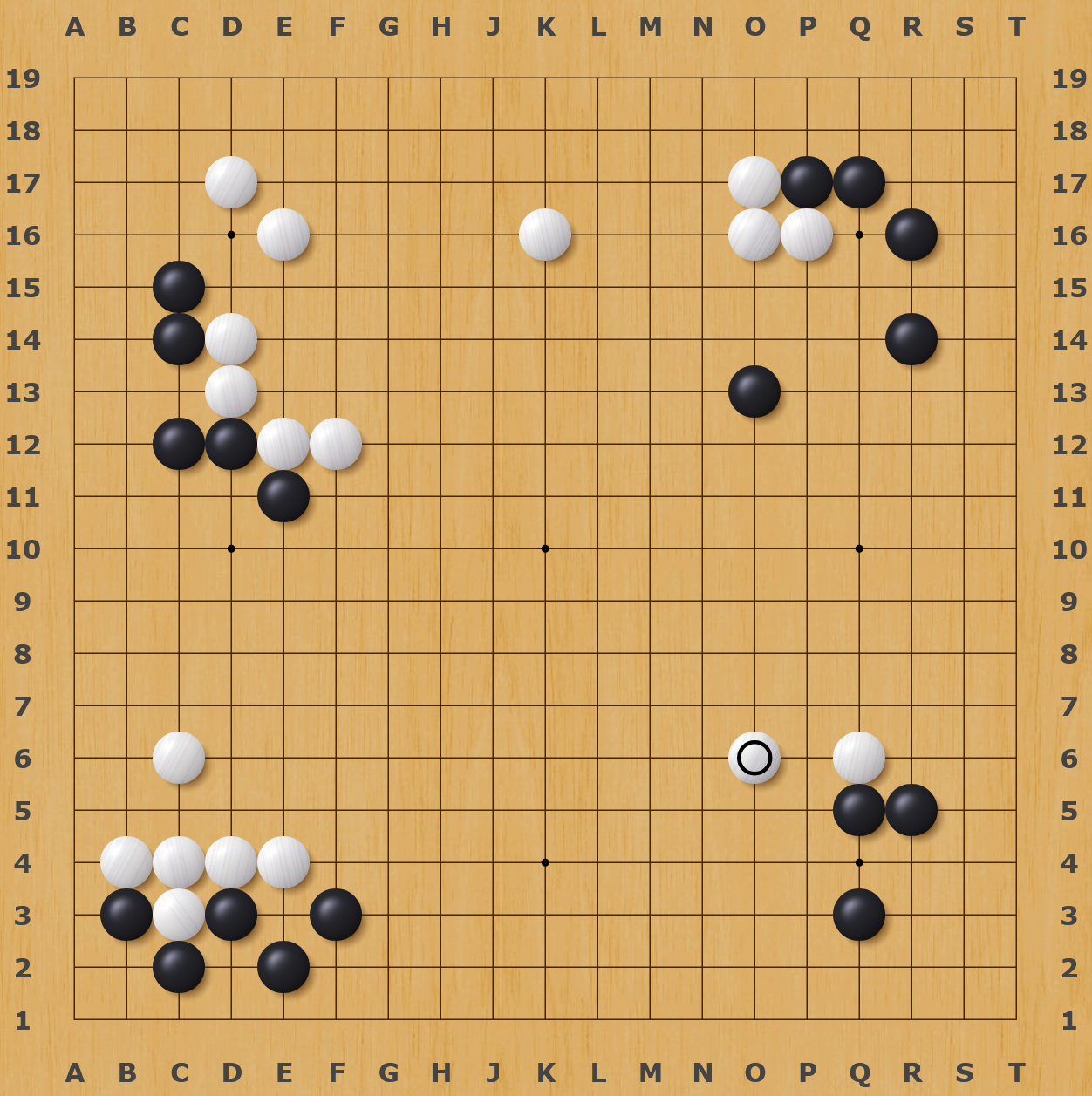

As an example, take this position on move 36 from a recent practice game of mine. According to an online database with 80000 games, this game became novel on move 7, thirty moves ago. However, neither player had up to this point played a move they had not memorised in its local context.

This means that the paper’s idea of looking at player behaviour after a ’novelty’ just doesn’t work in Go: the overwhelming majority of those ’novel’ decisions are still made in completely normal positions where all local variations are memorised by both sides. I see no evidence that these decisions are in any way less memorised than previous ones.

The other thing the researchers seem to misunderstand is that in the early game, there are almost always more than ten moves that are essentially equally favoured by both AI and humans. Moreover, humans are more or less aware of these AI preferences, beyond its top choice. This datapoint clashes with the idea of Shin et al.’s test measuring DQ after players deviate from the top AI choice. So long as this “sub-optimal” choice is still one of the almost-equally favoured moves, the opponent is likely familiar with it. They still can respond based on memorised patterns.

In general, it’s extremely easy for expert Go players to make decisions which are approved by AI in the early game, as they can rely on their memory and experience to navigate familiar local positions with little effort. This is why player performance according to the researchers’ decision quality index drops off after move 60, as local positions become more complex and interconnected. This is also why their argument that maintained improvement in decision quality in ’later’ moves (20-60) rules out memorisation is similarly flawed. Since it is not justified that experts are playing meaningfully novel positions during this part of the game, it becomes pointless to examine how decision quality varies between move 15 and move 30. To be fair, the authors do recognise in the appendix that their notion of novelty is a bit too simple for Go. However, they seem to underestimate just how misleading this oversimplification can get.

So… we aren’t getting better?

If you had asked me a year ago whether humans are getting measurably better at Go in the modern era, I would have said ‘probably a little bit’. I’m hence surprised and frankly a bit discouraged that human play after move sixty, in the relevant part of the game, doesn’t seem to have progressed since superhuman AI became available. Even worse, the way I’m most compelled to interpret the ‘improvements’ seen before move 60 is that humans can merely copy patterns suggested by AI. They don’t understand these patterns well enough to convert them into correct play in the key parts of the game. Expert humans’ median interaction with AI may well be superficial memorisation that doesn’t translate to meaningful understanding.

One explanation for humanity’s apparent stagnation may be that access to AI can hurt some players. A while ago I met an old acquaintance of mine on an online Go server. I remembered him as a stronger amateur player, but he was still weaker than some of my strongest students. I was surprised to find that he had achieved the highest possible rank on the server, demonstrating performance on par with that of active professionals. He credited his improvement entirely to AI, and explained to me in detail how he was using it to improve.

After our conversation, I checked out his games to find, unsurprisingly, that he was clearly cheating. Every. Single. Game.

This example is one of many I have found of cheaters who seem to believe that even if they’re consulting a superhuman AI while playing, they still have agency over which moves they play and are in some sense still playing and learning ’themselves’. This is cope. When cheaters consult an AI during their games, they tend to default to always playing its top suggested moves because their opinions are deeply influenced by the AI’s superior suggestion. The human is effectively disempowered, having few independent thoughts of their own, while the computer makes all the decisions.

I claim that this type of disempowerment is most pronounced in cheaters, as they tend to cheat because they’re already lazy in the first place. However, I think it’s a danger to anyone who chooses to study with AI: I feel myself fighting against the temptation to stop thinking every moment I’m using the AI on my computer.

These are hardly original observations. It is common to critique systems and the people within them for encouraging or participating in superficial learning. A mundane example of this is the memorisation of theory or problem solutions with no active, curious engagement. I rather would like to highlight how disturbing it is that this structural and personal habit of human laziness may be leading us to disempower ourselves in the face of AI. We’re living through the lamest version of cyborgism.

How do we actually get better?

While the data doesn’t seem to suggest that humans are improving on average, I am familiar with specific individual players who have clearly used AI to learn and improve. One question I’m working on answering is what separates a successful AI user and learner from an unsuccessful one.

Appendix: a technical remark on decision quality

I claimed earlier that game-critical decisions are generally made after move 60. Then why does Shin et al. 2021, which introduces an almost identical variant of the Decision Quality metric, show clearly that the worst DQ is seen between moves 30 and 60? I think the explanation for this lies in the way DQ is defined. Recalling the definition: \( DQI(a_{k}^{human}) = 100 - (Q(s_{k}, a_k = a_{k}^{AI}) - Q(s_{k}, a_k = a_{k}^{human})) \) we see that this is an affine function in terms of the drop in the Q-value (‘win-rate’). However, a drop in win-rate is not at all a linear indicator of move quality. On an empty board, my home computer gives white a 60% win-rate if ‘komi’4 is 7.5, but gives white a 44% win-rate if ‘komi’ is 6.5. This means that early in a game, mistakes that drop your expected score by one point will often lose you between 10% and 20% in win-rate. Consequently, fluctuations of win-rates between 30% and 70% are totally normal, even if the mistakes players are making are small in terms of the expected change in score. Let’s contrast this with a position where one side is already down to a win-rate of 10%. It is first of all impossible for that side to make a mistake which is 15% worse than the optimal decision. Additionally, they must make much worse moves that lose many more points to produce a further drop in win-rate. This is intuitive if you interpret the Q-value as an estimation of your winning chances. When the game is really close, a one-point mistake may be the difference between a win and a loss. However, if one side is already at a huge advantage, one-point ‘mistakes’ are not really relevant anymore.

Since games tend to have more extreme win-rate differences towards their end (as there is a clear likely winner), the DQ measure systematically overestimates the importance of human mistakes in the early stages of the game.

I would like to make clear that this ‘flaw’ in DQ as a metric isn’t that problematic if you’re comparing two moves played at the same stage of the game, as in that case an ‘8% mistake’ will have a comparable meaning in both situations. I think it’s rather problematic as a metric to compare moves played at varying stages, where an ‘8% mistake’ can mean vastly different things.

for reference, a usual game lasts around 240 moves if neither player resigns, and the game is played until territory can be scored. ↩︎

as was discussed earlier in this post, human improvement after AI does disappear after move 60, the researchers just chose to only consider data up to move 60 for their 2023 paper. ↩︎

as described in the appendix of Shin et. al ↩︎

komi is the artificial score added to white’s final score at the end of the game. It is meant to compensate the advantage black gets from playing the first move, and is set to either 6.5 or 7.5 in almost all competitive matches. ↩︎